2. Brief history of research on Namban Carta

The arrival of playing cards in Japan dates back to the late 16th century, in the midst of the provincial wars, when a fleet of Portuguese ships first came to Japan. Facts about this arrival were extremely difficult to obtain, however, due to the severe lack of historical materials, including documentary, material and oral evidence.

The set of 48 cards used for ‘carta’ games was initially believed to have come from the Netherlands. Thus, Miyatake Gaikotsu stated in his History of Gambling, published in 19231, that the foreign-born playing card had ‘come with the Dutch’, although the word ‘carta’ originated from the Portuguese.

This hypothesis changed drastically in 1924, with the publication of South Sea Chinyz by Shimura Izuru. In one of the articles included in the book entitled ‘Namban Carta, its Coming and Spread’2, Shinmura analysed the terms used for carta games and concluded as follows: ‘It may be said that the Japanese came into contact with card games in the late 1540s, during the Tenbun period. Furthermore, it might be assumed that the Japanese had learned about the games in the South China or Straits of Malacca area and brought them home, even before the arrival of the Portuguese’.

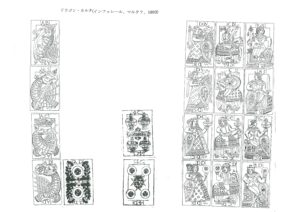

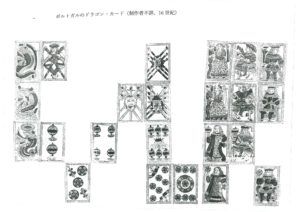

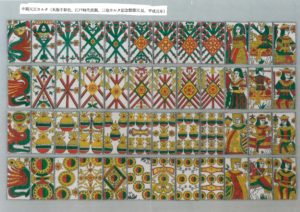

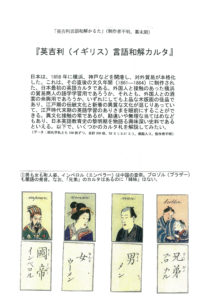

The next turning point came with a ground-breaking theory of Yamaguchi Kichirobei, a collector-researcher of the early Showa Era, disclosed in Unsun Carta3, a memorial publication printed as a manuscript by his son Yamaguchi Kakutaro in 1961, a decade after his death in 1951. In the darkest days of World War II, when academic research was severely hampered, Yamaguchi secluded himself in his house in Ashiya City, Hyogo Prefecture to re-examine the Shinmura Theory in detail. With the help of basic literatures available at that time, including A History of Playing Cards and a Biography of Cards and Gaming by Catherine Perry Hargrave4, he concluded that Japanese carta originated in Portuguese cards, which featured a dragon on the ‘ace’ of the four suit marks: Paus (sticks), Espadas (swords), Copas (cups) and Ouros (gold). This design, typical of the card-manufacturer Inferrera, must have been that of the original Namban Carta that came to Japan. Yamaguchi’s theory of ‘Inferrera cards as Namban Carta’ was a game-changer, and became the prevailing orthodoxy among researchers on the history of playing cards in the 1970s, with no one daring to challenge it.

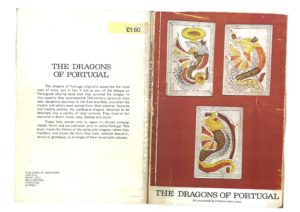

Subsequently, research on the history of Namban Carta became increasingly international. First, Sylvia Mann, a British collector-researcher, and Virginia Wayland, an American researcher, probed into the history of playing cards in Africa, Persia, India, East Asia, and Brazil in South America, where Portuguese traders were dominant during the Age of Exploration, determining that dragon cards, featuring the image of a dragon on the ‘aces’, seemed to have existed in all of those areas, whereas there was no sign of the existence of such cards in the regions colonised by Spain in that period. Thus, Mann and Wayland concluded that the dragons were not specific to the cards produced by Inferrera but were a feature common to the ‘regional pattern’ of cards made in Portugal: carried across the globe by Portuguese vessels, those dragon cards became popular in many parts of the world. This theory of dragon cards originating in Portugal pointed to a grand history of patrimony on a global scale. Their joint paper The Dragons of Portugal5, published in 1973, received enthusiastic acclaim among playing card researchers all over the world. Mann was surrounded by a large number of researchers including myself, who was staying in London at that time. Later in the same year, the Sylvia Mann School — a group of academic researchers who studied the history of playing cards by categorising them into regional patterns observed in different parts of the world — established a Playing-Card Society (PCS, which later became ICPS with the addition of “I” for ‘International’). I used to visit Europe and America to participate in the annual meetings of researchers organised by the Society. At her invitation, I also visited Sylvia Mann at her residence in southern England, on the outskirts of Rye, Kent County, to take a look at her immense collection of playing cards. Even now, I clearly remember the days when I indulged in conversations with Sylvia Mann and Adrienn Gurr, another IPCS member who was living at Mann’s residence. The conversations were so riveting that we literally forgot about eating.

At that time, Europe had another centre of playing card research: the Deutsches Spielkarten Museum, located in the suburbs of Stuttgart, in southern Germany. Margot Dietrich, the chief curator, was a central figure of ICPS along with Sylvia Mann. At the museum, I enjoyed the freedom to conduct completely unfettered research activities, just like its staff members. Thanks to her efforts, the museum organised an exhibition of East Asian playing cards in 1969, hired Gernot Prunner, an Austrian, and Detlef Hoffman, a German, to publish an academic index to the exhibition entitled Ostasiatische Spielkerten, and led research on the history of Japanese cards in Europe. I learned a lot from this publication, examined the museum’s collection of Japanese cards, and took every opportunity to engage in friendly discussions with Margot Dietrich and Detlef Hoffman, a researcher of my own age. As a fledgling learner, I was incredibly fortunate to meet with two of the world’s leading researchers of playing cards.

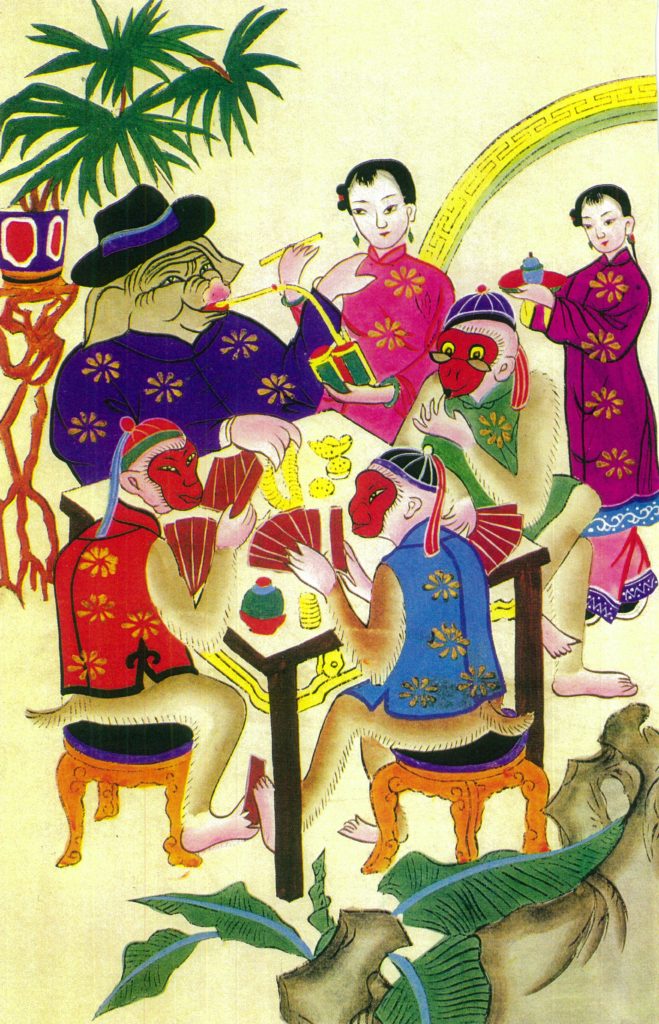

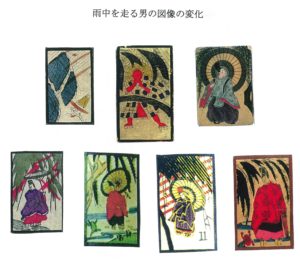

The historical drama of the Dragons of Portugal was to reach a climax here in Japan. Since dragon cards had completely gone out of circulation by the 19th century, we had no choice but to honour their memory with what little legacy was left. But one of their variants stood the test of time and was still used for games in an island country in the Far East! The discovery evoked a sensation among playing-card researchers rather like that of the palaeontologist who found that the coelacanth, an ancient fish, was still alive off the coast of the Comoros, or the archaeologist who discovered in the mountains of Sichuan Province in China trees of metasequoia, an ancient species he had only seen as fossilised remains6. The excitement was further enhanced by media reports on the discovery of hand-printed, edge-turned-up cards in Kyoto, still produced using the card-making technique that had reached Japan in the 16th century. International researchers, including Mann and Wayland, as well as Detlef Hoffman from Germany, Max Ruh from Switzerland, and George Hatton and Yasha Beresiner from the United Kingdom, successively visited Japan to conduct further research. I helped them with their activities, taking them to relevant sites such as a museum in Tokyo and the card manufacturer in Kyoto. The Wayland couple went as far as Hitoyoshi City in Kumamoto Prefecture to observe and record the activities of a local Unsun Carta playing group7.

Subsequent theoretical developments also came from the Sylvia Mann School. Trevor Denning, a British member of IPCS with a close working relationship with Mann and a friend of mine, conducted a study in the 1970s on the history of ‘regional patterns’ in the whole Iberian Peninsula including Spain, and found that dragons had been a common design element among the regional patterns found in many parts of the peninsula and overseas colonies, not only Portugal, until the late 16th century. In 1980, he disclosed his theory of dragon cards originating in the whole Iberian Peninsula in his book Spanish Playing-Cards8. His theory was widely accepted, prompting members of the Sylvia Mann School to start investigating historical materials to support or rebut the theory. The discoveries of material and documentary evidence in Spain, Italy and former Spanish colonies in South America also made substantial contributions. Thus, the history of playing cards revolving around the exploration of dragon cards developed into research on a global scale.

Around that time, Michael Dummet, another IPCS member and close friend of mine, published The Game of Tarot, a great piece of work completed with the support of Sylvia Mann, describing the history of Latin Carta in minute detail. As a world-class researcher on the modern history of philosophy, known for his study of Sigmund Freud and Friedrich Ludwig Gottlob Frege, Dummet developed a compelling argument based on his meticulous study of old documents in support of Denning’s theory, effectively reinforcing the basis of research in this direction. He continued to contribute to research in this area, publishing in 2004 A History of Games Played with the Tarot Pack: The Game of Triumphs.

Meanwhile, further investigation by Trevor Denning, the initiator of the theory, resulted in the discovery of card remnants, woodcut printing blocks and sheets of unfinished cards, all of which attested to the production and distribution of dragon cards starting in the 16th century in Malta, one of the key Mediterranean hubs of the United Kingdom of Aragon. He also discovered material evidence indicating that Inferrera itself was a Maltese card manufacturer. After all those discoveries, Denning reached the conclusion that playing cards had come to Malta in the latter half of the 14th century from Arabia, its close trading partner, from where they spread throughout the Kingdom of Aragon, and then across Europe. This historical theory of dragon cards spreading from Malta was all the more compelling because the so-called Latin Cara, comprising the four suit marks of Paus, Espadas, Copas and Ouros, were distributed in southern Italy, Côte d’Azur (Mediterranean coast of southern France), islands off the coast and the Iberian Peninsula.

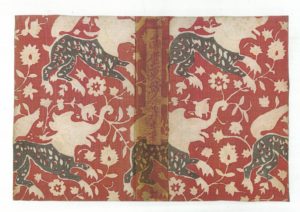

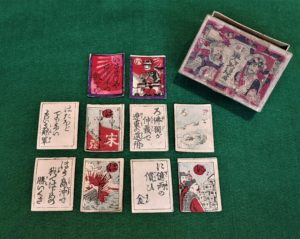

Later, critical discoveries were made in the field of Namban Carta research, which did not necessarily contradict the prevailing theories. In the 1980s, while an ancient church built in the 16th century was being dismantled in Antwerp, Belgium, they found woodblock-printed card waste used as wallpaper core. The news was brought to the attention of academia by Andre Kint, a Belgian member of IPCS9. The discovery effectively proved that a local card manufacturer had actually produced dragon cards by the 16th century, when waste from the production process was used as wallpaper and thus locked into the walls of the church. This material evidence only included a dozen cards, most of which were badly damaged. However, the remnants indicated that the cards had been produced with a sophisticated woodblock-printing technique, and had a striking resemblance to the Japanese Tensho Carta in design. The discovery made me wonder whether Namban Carta, brought to Japan on Portuguese vessels, had actually been produced in Belgium.

It is known that Belgium in the 16th century was a territory of the Spanish royal family, with a booming handicraft industry exporting products to Spain and Portugal. At that time, it was also a global centre of advanced woodblock printing, producing sophisticated products not found in Spain or Portugal. It is thus not surprising that the design of Belgian cards reflected the preferences of clients in Portugal, and that products marketed in Portugal travelled with traders all the way to Asia, specifically to the commercial hub of Batavia on the island of Java. It is not known whether the Portuguese vessels that came to Japan had carried the cards from the mainland or procured them at Batavia before sailing to Japan. Nevertheless, it was highly likely that dragon cards made in Belgium had been brought into Japan and subsequently called Namban Carta.

The production of playing cards has remained robust in Belgium, particularly low-priced cards for the general public. In the latter half of the 20th century, 1969 to be exact, the Nationaal Museum van de Speelkaart was established in the city of Turnhout, Antwerp Province, where one of the Belgium’s leading playing card manufacturers, Carta Mundi, is located. As a sponsor of the project, the city provided Huis metten thoren, an ancient building dating back to the 16th century, as the exhibition site, effectively ensuring that the museum would open. However, it remained impossible to collect any woodblock-printed dragon cards that the country had produced in the 16th century.

In 1991, the Miike Carta Memorial Museum (‘Miike Carta Museum’) was founded in Ohmuta City in Fukuoka Prefecture to mark the 450th anniversary of the local production of Miike Carta. In time for its opening, we eventually restored Miike Carta. As advisor to the Museum, I also travelled with municipal officials to Spain, Portugal and Belgium to explore historical materials on Namban Carta and their whereabouts, but came back empty-handed. I even visited the Nationaal Museum van de Speelkaart in Belgium to soak up the atmosphere of Namban Carta production in the 16th century, but without success. The true identity of Namban Carta remained a mystery. Many years have passed without any significant developments.

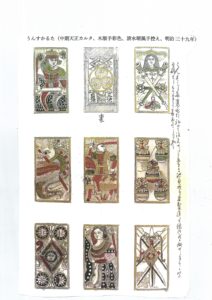

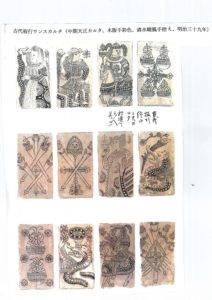

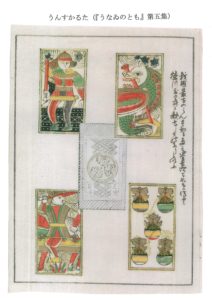

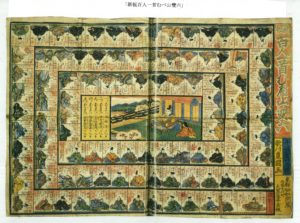

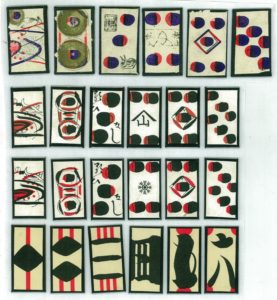

The exploration of historical materials on Tensho Carta made some headway earlier in the 21st century. Unsun Carta by Yamaguchi Kichirobei had included some lines on Unsun Carta cards presented at a meeting of Shukokai, a gathering of historical material collectors who met regularly in Tokyo in the first half of the 20th century, and reported in the fifth volume of its journal Shuko. This apparently referred to a set of 48 Miike Carta cards from the 17th century, kept at Matsunoya Bunko owned by Yasuda Zenjiro, founder of the eponymous zaibatsu. The cards could no longer serve as material evidence, however, having been destroyed by fire in the Great Kanto Earthquake. The only historical material left was imitative drawings of five of the cards (recto and verso) by Shimizu Seifu, available in the same volume of Shuko.

In the early 21st century, the original hand drawings of Shimizu Seifu appeared on the old book market. Recognising their value as a historical material, a group of like-minded researchers of the history of dolls and toys purchased the drawings for storage in the reference room of Yoshitoku, located in Asakusabashi, Taitou City, Tokyo. The material actually contained imitative drawings of nine of the Miike Carta cards (one of which depicted the back side) which appeared to have been reported in Vol. 5 of Shuko. In addition, the material included on another page the images of 12 different Tensho Carta cards kept at Yasuda Matsunoya Bunko. Thus, we had 20 images of the front side and one drawing of the back side in total. Given that the visual evidence available on block-printed Tensho Carta from the 17th century, or Miike Carta, had been limited to the Warrior of Paus, kept at the Tekisui Museum of Arts, and the aforementioned drawings of four cards found in Shuko, including only two images of the back side, the discovery presented an opportunity for the researchers of Miike and Tensho Carta. We were busy studying this new evidence when new information on ‘dragon cards’ was made public by the Nationaal Museum van de Speelkaart.

¹ Miyatake Gaikotsu, “History of Gambling”, Hankyoudou, 1923, p.18.

² Shinmura Izuru, ‘Namban Carta, its Coming and Spread’, in “Namban Sarasa”, Kaizousha, 1924, p.103.

³ Yamaguchi Kichirobei, “Unsun Carta”, Riichi (Private Edition), 1961.

⁴ Catherine Perry Hargrave, “A History of Playing Cards and a Bibliography of Cards and Gaming”, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1930.

⁵ Sylvia Mann & Virginia Wayland, “The Dragons of Portugal”, Sandford, 1973.

⁶ Saito Kiyoaki, “Metasequoia”, Chuoukouronnsha, 1955.

⁷ Harold Wayland, Virginia Wayland, ‘From Omble to Unsun’, in “Bessatsu Taiyo Iroha Carta”, Heibonsha, 1974, p.188.

⁸ Trevor Denning, “Spanish Playing-Cards”, IPCS, 1980.

⁹ Andre Kint, “An Important Discovery in Antwerp”, IPCS Journal Vol.13 No.2 (1984), p.45.