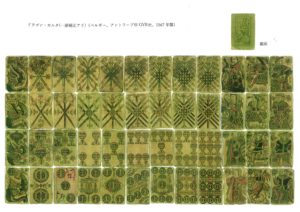

4. Iconographic characteristics of restored Namban Carta

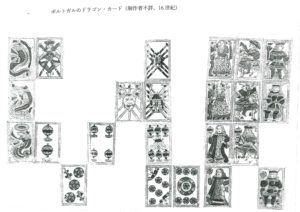

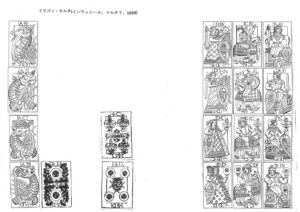

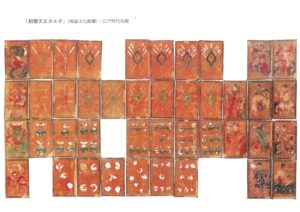

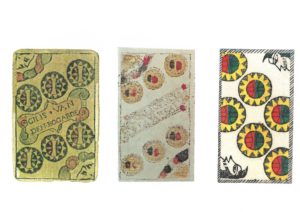

With this discovery, researchers of the history of playing cards now have a basic collection of material evidence from the Age of Exploration in the 16th century including: (1) 44 dragon cards manufactured in 1567 by Gilis van den Bogarde Anveris (GVB), a card-maker based in Antwerp, Belgium; (2) printed waste paper for 13 dragon cards produced by CF, a company located in Antwerp, Belgium before 1574, when it was used as wallpaper of a church; (3) three uncut sheets (two for the front side and one for the back side) for a set of 48 dragon cards, produced circa 1587 by Francisco Flores, a company located somewhere in Spain; (4) 23 dragon cards produced in the 17th century by an unknown Portuguese manufacturer; and (5) 19 dragon cards manufactured in 1693 by the Maltese manufacturer Inferrera. Japanese playing cards, such as Miike Carta and Tensho Carta, can now be positioned in the framework of those world trends. The whole picture highlights the critical importance of the recent discovery and disclosure.

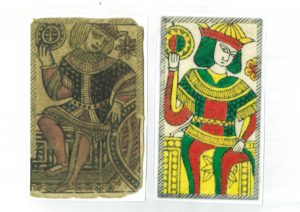

The newly discovered cards were produced in 1467 by Gilis van den Bogarde, an Antwerp-based company. It should be noted that some of the cards are printed in reverse, thus producing mirror-reversed images. This strange error cannot happen with the traditional Chinese-origin art of woodcut used for Japanese carta — carving all the images for a set of cards on a solid wooden block of wild cherry tree, for example, before printing. But it can happen with the woodblock printing technique that prevailed in Europe after its invention by Johannes Gutenberg, i.e. a cut end block-printing method of carving the image of each card on a small piece of wood and aligning all 48 pieces on a smooth surface before printing. The Gutenberg Museum in Mainz, Germany includes an exhibit of printing blocks for cut end block-printing to demonstrate how ancient playing cards were produced. With this method, worn printing blocks were replaced in turn by newly carved blocks. The original image for producing a new block was printed using the old block. The image thus obtained was attached in reverse onto a piece of wood for carving. Apparently, this process of reversing the original print was often neglected, resulting in mirror-reversed images for some of the 48 cards that made up a set of carta. In other words, the existence of this error proves that the cards were produced with the cut end block-printing method.

The size of the cards, about 9 cm long, also has important implications. As the first researcher to point out the changing dimensions of Japanese cards after importation from abroad, I presented a hypothesis based on an examination of various historical materials that playing cards made in Japan had been made smaller over the years. Indeed, Namban Carta, as it came to Japan in the latter half of the 16th century, measured about 9 cm long, just like tarot cards today, only to be reduced to some 7 cm in the first half of the 17th century, as was the case with the medium-sized Japanese cards such as the Hyakunin Isshu Poem Cards, and then to some 5 cm during the ‘carta fad’ in the last quarter of the 17th century (early Edo period), as could be seen among the popular small-sized wood-block cards such as Flower Carta and Gambling Carta. The newly discovered Namban Carta is 9.2 cm long and 6.0 cm wide. I am delighted to see this strong support for the credibility of my hypothesis.

The iconography and pattern of the discovered cards present some notable characteristics. First, each of the ace cards contains an icon of a dragon, hence the term ‘dragon cards’.

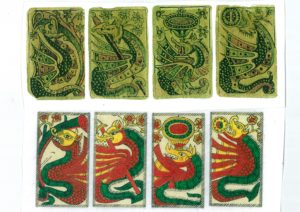

Of the four ‘dragon aces’, only the ace of Paus carries a reversed image. In the Japanese Tensho Carta, the ace of Paus points to the left, as with the other three aces, whereas the suit mark points to the upper right. As for the newly discovered cards, the dragon points to the right, and the Paus to the upper left. The same difference may be observed in other cases, including the dragon cards in the ex-Sylvia Mann collection reportedly produced in Portugal in the 17th century (the fourth item listed above). Whether out of indifference or generosity, it seems that the dragons were looking in either direction depending on the manufacturer in 16th century Europe.

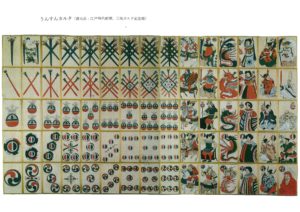

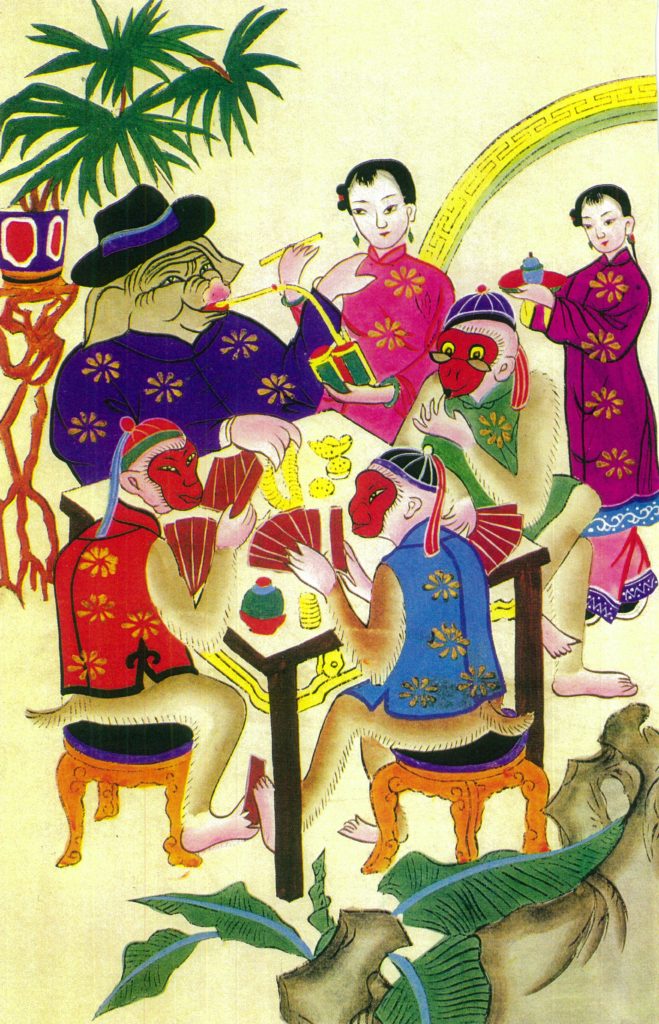

Some remarks should be made on the term ‘dragon’. The playing cards that came to Japan included both the European Dragon, as observed in the woodblock-printed Namban Carta and Tensho Carta, and the Chinese Dragon, as observed in the mainly hand-drawn Unsun Carta. The European Dragon is an embodiment of an elderly bat, which has wings but does not spit fire. In contrast, the Chinese Dragon is an incarnation of an elderly snake, which does not have wings but ascends to heaven by spitting a whirlwind of fire, hence its byname of ‘fire dragon’. It is for this reason that the dragon of Tensho Carta has wings while that of Unsun Carta is surrounded by fire. This is a typical difference that warrants further research on its implications.

Traditional research on the history of playing cards ignored this critical difference, probably due to the lack of comparable material evidence. My theory is that the cards with web-winged dragons, including those of Namban Carta, came directly to Japan aboard European vessels (directly imported) whereas the cards with fire dragons first went to other parts of Asia, were cultivated and localised into the Chinese Dragon in the Chinese community in Southeast Asia or the mainland, then ended up in Japan (indirectly imported). Indeed, I was the first to put forward the hypotheses that the two types of cards, one carrying the European Dragon and the other the Chinese Dragon, implied the existence of multiple routes by which European cards travelled before coming to Japan, and that the cards with fire-spitting dragons might even have originated in the Chinese community11. This is why I use the term ‘dragon’ for both types of cards, rather than the Chinese word ‘Loong’.

The second issue concerns the colouration of Paus and Espadas. The two suit marks are easily distinguishable in Tensho Carta, with Paus in green and Espadas in red. But this is not the case with the Flores cards kept at a museum in Seville, Spain (the third item listed above), as mixtures of red and green are used for both Paus and Espadas. In the case of the dragon cards made in Belgium, the colouration of the two suit marks is far more distinct, with Paus mostly in green with red fringes, and Espadas clearly printed in black and red. Thus, there are differences in colouration even in Europe, depending on the time and place of production.

The third issue concerns the design of the profiles appearing on the six of Ouros. The profiles, most often located in the upper left and lower right of a European card, are placed in the upper right and lower left of Tensho Carta, which means that the Japanese card was a reverse print of the European card. Moreover, the six gold coins on this card, drawn from the upper right to lower left of the European cards listed as items (2) and (3) above, are aligned from the upper left to lower right of Tensho Carta. Since it is hard to imagine that the Japanese cards were intended to demonstrate originality, it is likely that the Namban Carta that reached Japan happened to include one of those reverse-printed cards with six gold coins aligned from the upper left to lower right. In light of the space left in this card, we can assume that the profiles were placed in the upper right and lower left. This is another case of reverse image by mistake.

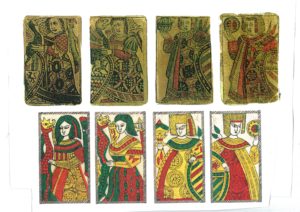

Now let us turn to the three court cards: Sota, Horse and King. In Europe, all of the four Sotas invariably face to the left, as is the case with the newly discovered Namban Carta. In contrast, only the Sota of Ouros faces to the right in the Japanese Tensho Carta. Was the image reversed in Japan? As regards the Horse, the reversal is observed in two of the four suit marks, namely Espadas and Ouros. As for the King cards, the physiognomy of the king is interesting. The king in Tensho Carta is young and childlike, with a striking resemblance to the king depicted in the dragon card remnants used as wallpaper for the church in Antwerp (item (2) listed above). In contrast, the king in the newly disclosed set of playing cards is depicted as a more mature adult king. We may conclude that the physiognomy of the king differed depending on the manufacturer or the place of production.

Finally, the artwork on the flip side is also intriguing. There we find the image of a handsome young man characteristic of the renaissance period, Antwerp being a hub of the Northern Renaissance. The interesting feature of this image is that it does not have the appearance of a medieval religious painting of the 15th century but reflects the aesthetics of Sinjoren (inhabitants of Antwerp) in the 16th century. In Japan, a groundless hypothesis used to circulate that the portrait of Jesus Christ on the back side of Namban Carta was replaced in Tensho Carta in order to emphasize that the playing cards were not a means of disguising Christian beliefs. This hypothesis was rebutted once and for all by the recent discovery.

The disclosure of the new material also provides decisive historical evidence regarding the colouration of the Belgian dragon cards. As had been assumed, they were coloured red, yellow and green. The distribution of the three colours often differs from that of the restored Miike Carta, particularly for clothes. But the variation might be attributed to differences among producers. In any case, the assumption that the three pigment colours were used for dragon cards turned out to be true. Gold and silver colours seem to have been added to the Japanese Tensho Carta from an early stage, as this was not the case with the original Namban Carta. In other words, the gold and silver colouration was a technique specifically developed in Japan.

¹¹ ●●