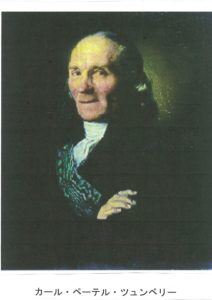

(1) Carl Peter Thvnberg, the first person to present Japanese carta to the world

The first European to mention ‘carta (playing cards)’ in Japan was Carl Peter Thvnberg (Thumberg, Toumberi, etc.)¹, who came to Japan after being hired as a medical doctor at the Dutch trading centre in Dejima, Nagasaki. Thvnberg arrived in Japan in 1775 and in 1776 travelled to Edo as a member of the Dutch envoy to have an audience with the 10th Shogun, Tokugawa Ieharu. Thvnberg exploited this opportunity to deepen his experience, met Japanese scholars of the Dutch language and medical doctors during his travel and stay in Edo, and left Japan at the end of the same year. During this short stay, Thvnberg conducted acclaimed research on Japanese plants and pioneered the introduction of Japanese vegetation to Europe. He also had a significant impact on botany among the Japanese, and today, Thvnberg is renowned as the founder of Japanese botany.

After returning to Sweden, Thvnberg published a diary in Swedish of his travels to Africa and Asia, leading to Japan². This travel record on mysterious countries in the Far East resonated greatly and French, English and German translations of the diary were published. In addition, a French book edited separately only about Japan, Voyages de C.P. Thumberg, au Japon³ was published in 1796 in France. Much later, in 1928, it was translated into Japanese and published as a book in Ikoku Sosho (Series of Exoticism), titled Thvnberg’s Travel Note of Japan⁴. Today, if you search for ‘Thvnberg Nihon Kiko (Travel Note of Japan)’, the original author will be displayed as Thvnberg, but strictly, this is not a complete Japanese translation of the French version of Thvnberg’s original book, but only a Japanese translation of a long French summary by L. Langles.

On page 360 of this Japanese translation, Thvnberg touched on carta in Japan. He was leaving Nagasaki for Edo in the spring of 1776, and had boarded a ship in Shimonoseki, Yamaguchi Prefecture, which anchored for a few days to wait for fair winds at the nearby port of Kaminoseki. Let us hear the story from the translation of Yamada Tamaki.

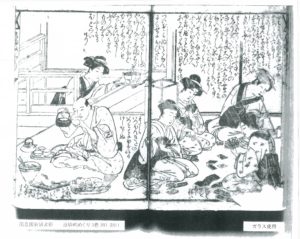

‘Japanese people don’t like to play carta very much. It is strictly prohibited by the government. Sometimes they play carta on board, but never on land. The Japanese carta is two puth (inch) vertically and one puth horizontally. It is made of paper, one side is black, and the other side is painted in various disorderly colours. There are 50 cards in a deck. When playing carta, some cards are divided into several pairs of piles, and money is put on them. The persons playing carta pull out the cards one by one, turn the cards upside down, and the one who gets the most beautiful pattern wins. This gambling is quite similar to the European Petits Paquets.

This description of Thvnberg is a valuable eyewitness account of a gambling card game of Japan by a foreigner at the time, but usually the Japanese would not have played gambling card games in front of a Dutch doctor. It happened during a boat trip with the Japanese in a closed space, staying in a harbour for a long time to wait for fair winds. Thvnberg’s knowledge came from this exceptional experience of sharing time with Japanese card game players in an unusual setting. It is likely that Thvnberg did not participate in the game, but watched carefully and perhaps touched the cards.

In Yamada’s Japanese translation, Thvnberg describes three main points. The first is the situation of gambling card games in Japan. ‘Japanese people don’t like to play carta very much. It is strictly prohibited by the government. Sometimes they play carta on board, but never on land’. The second is the cards used for carta games, ‘The Japanese carta is 2 inches in length and 1 inch in width. It is made of paper, one side is black, and the other side is painted in various disorderly colours. There are 50 cards in a deck’. The third is the technique of playing card games. ‘When playing carta, some cards are divided into several pairs of piles, and money is put on them. The persons playing carta pull out the cards one by one, turn the cards upside down, and the one who gets the most beautiful pattern wins. This gambling is quite similar to the European Petits Paquets.

The first part of the Japanese translation is obviously contrary to historical fact. In Japan, gambling card games were prohibited on both land and water, and there was no time or place when or where Japanese people ‘never played’ gambling card games on land. However, this is not clear in Thvnberg’s description. Thvnberg wrote only about events on a ship anchored at Kaminoseki port , but not the general theory about the situation of gambling carta games in Japan. However, the French summary version of the book on which the translation into Japanese was based was published by reorganising Thvnberg’s diary by items, and many parts differ from the original due to the summarizing style of the editor, L. Langles. The only fact is that Japanese crew members of the ship on which Thvnberg was on board played carta at that time on the ship but not on land. The overly-generalised French version led to the Japanese book explaining that gambling carta games were generally done only on ships, causing misunderstanding. The Japanese translation of this part is due to the misunderstanding introduced by the double translation from the original Swedish book, via a summary in French, into the Japanese translation. The responsibility for this misunderstanding is not the fault of Yamada, who merely translated into Japanese.

The second point that Japanese carta contained 50 cards in a deck is almost accurate. The description ‘2 inches in length and 1 inch in width’ is also an accurate observation, because the ratio of length to width of early Japanese carta was roughly 2:1. However, the Japanese translation ‘it is made of paper, one side is black, and the other side is painted in various disorderly colours’ is strange. This mistranslation happened because the word describing the suit marks of this carta was misinterpreted. The term ‘suit marks’ was translated as the equivalent ‘les couleurs’ in French, but Langles misunderstood this to simply mean ‘colours’ and used almost the same word ‘bigarrures’. As a result, the original meaning of the Swedish word could not be understood at all because it was translated one more time improperly as ‘disorderly colours’ in the Japanese translation. It should have been written as, ‘It was made of paper, the back side was black, and each surface had one of four different suit marks’. If this misunderstanding is corrected, Thvnberg’s description clearly conveyed the characteristics of carta in Japan at that time. The misunderstanding was an accident that occurred in the process of translating the French summary into Japanese.

The description ‘some cards are divided into several pairs of piles, and money is put on them’ shows the rule of the Kabu Carta game. In this game, it appears that the cards are ‘divid[ed] into several pairs of piles’ because the game starts with the dealer distributing one or two cards in turn in front of each player. In addition, if the participants bet money, the wager should not be placed on the distributed card, but in the space before or next to it. However, this small difference in explanation is not a major problem. The following sentence ‘The persons playing carta pull out the cards one by one, turn the cards upside down, and the one who gets the most beautiful pattern wins’ is an inaccurate Japanese translation of ‘The participants of the game draw one card or more, place them on the table facing up, and the participant who has the most beautiful pattern wins’. This sentence can be interpreted in various ways: the dealer at the centre of the game distributes additional cards one by one to players from the pile of cards remaining at hand, or the dealer places one card on the table for himself at the end of the game and exposes it to the place. Gambling card games are played in different ways by different players, so the meaning of the short sentences in the diary is not precisely clear; it cannot be definitively stated that the translation is incorrect.

Also, ‘the most beautiful pattern wins’ (la plus belle a gagné) is a mysterious sentence. I cannot decide whether it means that the player who got the most excellent (beautiful) card like ‘Dragon-ace’ should

be the winner, or that the player who got the most beautiful combination of distributed cards should be the winner. I do not know what it means to win by this rule of the game, so I cannot judge it as right or wrong. Usually, in the Kabu Carta game, the winner is not restricted to one participant (dealer or player), but many winners and losers happen between each player and dealer. Thus, ‘the most beautiful pattern (one person) wins’ is unlike the Kabu Carta and more like the trick-taking game called Awase Carta in which one player wins for each turn (trick). It is difficult to understand the real meaning of this sentence.

Thvnberg states that this Japanese carta playing technique is ‘quite similar to the European Petits Paquets’. However, the playing technique Petits Paquets is not well known, and is not common in Europe. Rather, it is a local game technique in France, because Langles did not say in the French version ‘European Petits Paquets’, instead he said ‘our (French) Petits Paquets’. In Thvnberg’s Swedish original, he mentioned a Swedish playing technique named ‘Sala bybika’. I do not know this technique at all, and cannot explain the relation between ‘Sala bybika’ and the playing technique called ‘Petits Paquets’.

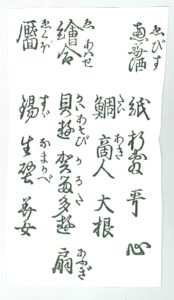

This is an outline of Thvnberg’s introduction to carta in Japan. It is very short, but I think the point is that he properly introduced an unknown carta game culture that he had discovered for the first time. At the end of his Swedish book there is a Japanese-Swedish dictionary. Unfortunately, this dictionary is deleted in Japanese translations, but it contains some very interesting words. For example, the word ‘card’ is translated as the meaningless Japanese word ‘Semek-u, niskaka’, but it is understandable because Thvnberg wrote in another part ‘Karta-utsu, bakkutsu, bakkutji-utsu’ as the Japanese corresponding to the Swedish word ‘play with cards’. These Japanese words mean ‘play carta’, ‘do gambling’, and ‘play gambling’. In carta games, Thvnberg’s understanding is appropriate because to describe the actions of players in card games he used the word ‘throw’. In Japan, in card games like Hyakunin Isshu Carta and Iroha Carta, which are both for women and children, the action is not called ‘utsu (throw)’ but ‘toru (take)’. Thvnberg sometimes associated ‘carta’ with ‘bakuchi (gambling)’, but on the other hand he associated ‘a man who plays dice games’ with ‘bakutsi utsi (gambler)’. For Thvnberg, the Japanese word ‘bakuchi’ is polysemous.

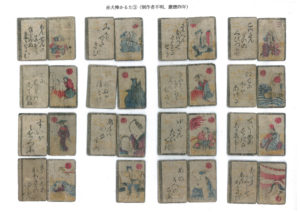

Yamada Tamaki’s translation of the long French summary by L. Langles has another problem. In the Table of Contents page of the book, Yamada referred to carta in ‘Chapter 21 Japanese festivals, amusement games’ and indicated ‘Hanahuda (360)’ (360 is the number of pages in the book). If this came from the original book of Thvnberg, it is a very important reference for the history of Hanahuda. If a carta-based game using Hanahuda cards was played by Japanese crew on their ship in the mid 18th century, and if there was a foreigner who actually witnessed the game, then it is the oldest document stating that the Hanahuda card game was popular in the mid 18th century, and is likely the oldest surviving document on the Hanahuda game. I believe that Hanahuda was invented for high-society people at the end of the 17th century and spread to upper-class society in the mid-18th century. Thus, this may be a valuable historical document supporting my theory, confirming that the Hanahuda card game already existed at this time.

Unfortunately, I cannot determine whether the gambling game was played by male seamen on ships at that time. The word ‘Hanahuda’ does not exist in the Table of Contents of L. Langles’s French summary book, which was the original of the translation by Yamada, nor the English version of Thvnberg’s original work that Yamada referred to, nor the original Swedish work of Thvnberg which Yamada left unsavable as unmissable. In other words, it is strange that the translator, Yamada, added the word to the Japanese version by himself, and so the Japanese word ‘Hanahuda’ was added to the Table of Contents.

Moreover, Yamada seems to have had only an image of Hanahuda in his head when faced with the word ‘carta’ during the translation of this book. In the mid 20th century in Japan, the gambling carta Awase Carta, Mekuri Carta and Kabu Carta disappeared from society among common people and shifted to the underground criminal world. Thus, polite citizens like Yamada did not have any information or knowledge on traditional gambling carta. For them, the word ‘carta’ could be imagined only as Hanahuda. As there were still some other carta for woman and children such as Hyakunin-Isshu Carta and Iroha Carta, Yamada might have thought that the word ‘Hanahuda’ was better than the broader word ‘carta’ to help Japanese readers imagine the old gambling carta.

¹ The name is difficult to pronounce. In the first half of the 20th century, ‘Tunberg’ was a German-style spelling and reading, and in the past, there were many examples of ‘Toumberi’, but a project at the Swedish Embassy in Japan in 1995 used ‘Thvnberg’, and in Japan, the records of the Imperial Household Agency concerning viewing of the Emperor and the Empress wrote ‘Thvnberg’. In the future, this will be the dominant notation and so is used in this paper.

² Carl Peter Thvnberg, ‘Resa vti Europa, Africa, Asia förrattad ären 1770-1779’, Uppsala, Joh. Edman, 1788.

³ Voyages de C.P. Thunberg, au Japon, par le Cap de Bonne-Espérance, les isles de la Sonde, & c. Traduits, rédigés et augmentés de notes ... particulièrement sur le Javan et le Malai, par L. Langlès, ... Et revus, quant à la partie d’histoire naturelle, par J. B. Lamarck, ... (1796).

⁴ L. Langles (translated by Yamada Tamaki), ‘Ikoku Sosho Thvnberg’s Travel Note of Japan’, Shunnan Co., 1928.